As maternity wards continue to shutter across rural America, Lander’s Sagewest hospital has held onto its birthing facility — the only one in Fremont County’s 9,266 square miles. But it has lost the confidence of some of the community it serves.

Perched on a rise that overlooks leafy neighborhoods and sweeping Wind River Range foothills, the hospital has served Fremont County for nearly 40 years. Over the last decade, a flurry of mergers and acquisitions, consolidation and staff turnover — along with high-profile safety failures — have eroded SageWest’s reputation in both Lander and Riverton where it operates hospitals.

SageWest Health Care closed the Riverton labor and delivery unit in 2016 when it consolidated its Lander and Riverton campuses — a decision many residents of the larger town decried. In 2017 the Wyoming Department of Health found the Lander hospital had failed for years to properly sterilize surgical tools and equipment. In 2020 the Lander facility failed a safety inspection, according to reports, after a psychiatric patient gouged out the eyes of another patient. The victim died shortly after the attack.

Meantime, the organization’s executive leadership has turned over and staff have resigned, in some cases replaced by traveling health care providers.

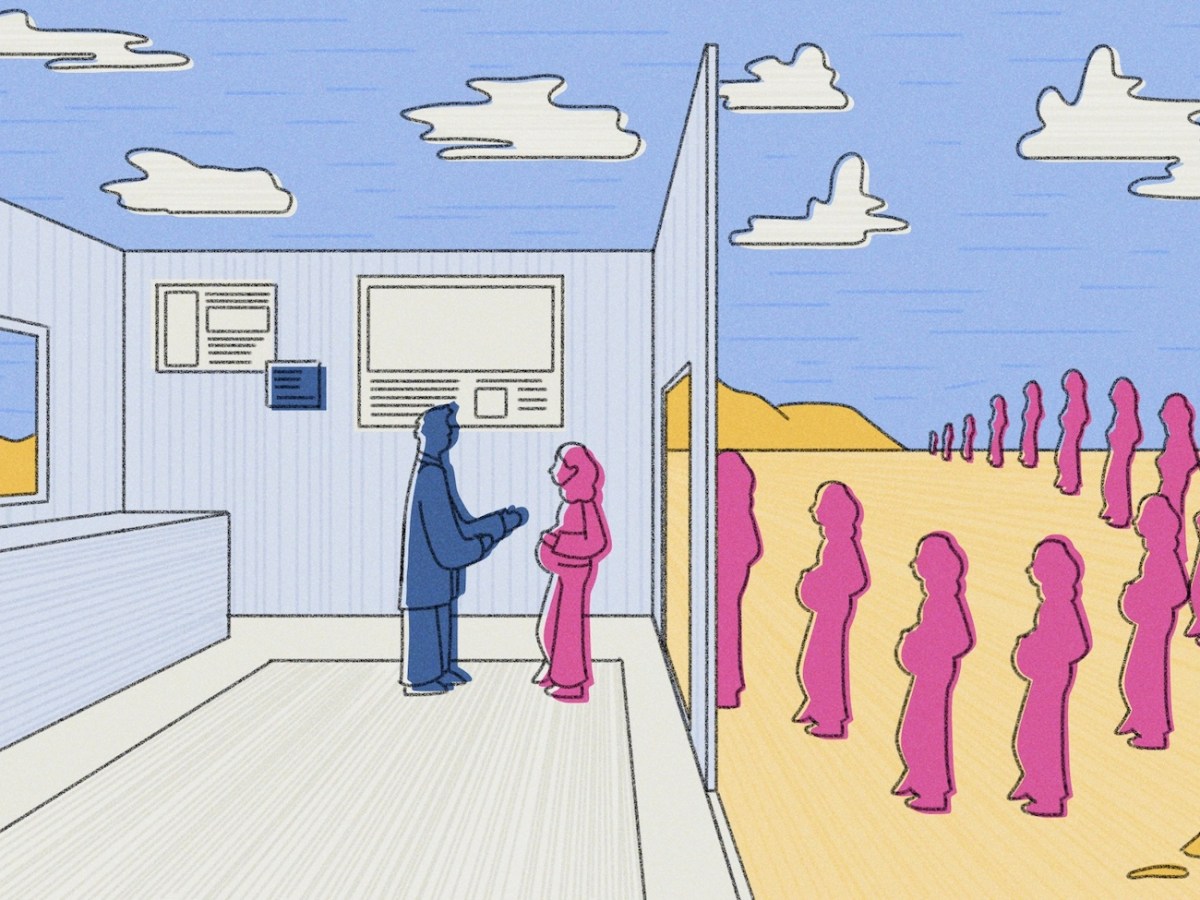

One result, physicians and moms told WyoFile, is that expecting mothers are traveling elsewhere for maternal care in increasing numbers.

“It’s one thing to have a hospital where you can deliver your baby, but if you don’t have faith that it’s top-quality, state-of-the-art and bringing in great doctors, there’s a lot of incentive to look elsewhere,” explained Lander mom Kristen Gunther, who did just that when she became pregnant with her second child and discovered her former providers, whom she was very happy with, were no longer delivering at SageWest.

“I think it’s not a secret that this hospital has challenges,” she added.

SageWest Health Care CEO John Whiteside does not contest that assessment, but maintains SageWest is a “great hospital” with “great staff.”

“I don’t think any CEO before me did anything purposefully to create a negative reputation,” he said. “I don’t think any doctor has ever done anything purposefully to create a bad reputation. But we have earned a bad reputation.”

The hospital is working to listen to the community and right the ship, he said. For example, it has recruited a new obstetrician who will start next year. The addition will be welcomed by patients and providers alike in this community where a single OB provides services for a general population of nearly 40,000 people.

But given the scope and systemic challenges inherent to rural health care, it won’t provide an instant fix. In the meantime, many pregnant patients are risking travel for out-of-county and even out-of-state care. Hoping to stem that tide, and address other concerns, a group of Riverton citizens is closing in on a yearslong effort to build their own hospital.

Building their own

Riverton and Lander’s hospitals were separate entities for many years until 2014, when they merged to form a single system called SageWest Health Care. SageWest was a subsidiary of the Tennessee-based rural hospital chain LifePoint Health. In 2016, Lifepoint consolidated the Lander and Riverton campuses. That transition included closing down Riverton’s labor and delivery unit, among other services.

Patient-safety concerns spurred that decision, Whiteside said, though it was before his time. “In order to provide the best, safest care for the patients, they consolidated.”

Critics, particularly in Riverton, were skeptical of LifePoint’s justification, seeing instead cost-cutting at the expense of community needs.

In late 2021, LifePoint merged with Kindred Health under an acquisition by the private equity firm Apollo Global Management. Today, the hospital is part of Scion Health, a network of nearly 80 hospitals across 25 states with headquarters in Kentucky.

Though under the umbrella of Apollo, and often criticized as a private-equity-firm-run operation, Scion is an independent company that endeavors to make SageWest a vibrant hospital, Whiteside stressed.

“We’re a new company. We’re Scion, we’re not LifePoint,” he said. “Everything has changed.”

Critics, however, say SageWest’s reluctance to invest in equipment, maintenance and a local workforce makes it impossible to attract and retain sufficient numbers of long-term doctors, nurses and other staff. Chase Ommen, a nurse midwife who worked in the hospital’s labor and delivery ward, said the support system for employees plummeted after the 2016 consolidation.

The loss of an OB ward and other services in that consolidation so upset Riverton citizens that a small group of residents organized to build their own hospital.

After more than five years, the Riverton Medical District is nearing the end of an immense feasibility, fundraising and planning effort to build a community-owned hospital. Along with millions of dollars in private donations and a $10-million state allocation of federal stimulus funds, the group secured a $37-million USDA Rural Development Loan and a building site that includes four acres donated by the Eastern Shoshone tribe. By late summer, crews had started soil work in preparation for building the 70,000-square-foot facility on the east end of town.

The district is partnering with the Billings Clinic and plans to be an affiliate of the larger health care company. The association with the Montana-based system will offer access to numerous key resources and, stakeholders hope, help recruit top-notch talent.

The endeavor has received national news attention. The very fate of the Riverton community is at stake, board members say, making it worth all the effort.

“This whole initiative is fundamental to health care and viability of this town,” said Dr. Roger Gose, a retired internist and medical district board member.

Adequate health care is crucial to attracting young families, retirees and businesses, and it has trickle-down effects that benefit a town’s economy, board members say. Fremont County consistently ranks as having the lowest community health scores in the state. And “adequate” certainly includes a birthing facility, board members maintain.

“We’ve had more than one person say to us, ‘When will the hospital be built? I’m not having another baby until we have a hospital back in Riverton,’” said Cindy McDonald, another district board member.

By board chair Corte McGuffey’s calculation, the last babies born in the Riverton hospital are now in second grade. That lapse in service, he said, is “ridiculous.”

“We’ve come up against some huge roadblocks, but we’re just like, ‘what is happening right here is just not good enough,’” McGuffey said.

The hospital consolidation preceded a spike in Fremont County medical transports, according to a Riverton Medical District report based on Wyoming Health Department numbers, with interfacility ground and air patient transports from SageWest in Lander or Riverton to other facilities doubling between 2014 and 2019.

Many Riverton residents also go elsewhere of their own volition, board members say, both for specialists and lower-cost options.

The Casper Star-Tribune reported that a 2019 study found SageWest charged private insurance more than eight times what the facility was paid by Medicare — the highest relative price in the state.

“Our prices can be high,” SageWest CEO Whiteside said, but noted that investor-owned hospitals have such different financial structures that it’s not fair to compare them to community-owned facilities. “Our prices are not expensive if you’re a commercial patient, because your insurance is covering that.” The hospital has payment plans on offer, he added.

Rather than focus on profits, Riverton board members say, the district’s goal is to create a hospital driven by quality.

The current timeline calls for groundbreaking in 2024, and the district hopes the new facility will open in spring 2025. Plans include two labor and delivery suites, as well as a lab, radiology unit, emergency department, pharmacy and 24/7 surgery. The facility is designed to be expanded in the future.

Providing and delivering

If a woman in Fremont County is in labor, she can deliver at SageWest Hospital in Lander 24/7. The OB shortage means there’s a chance she will do so with a traveling doctor that she’s likely never met — a scenario that many expecting mothers aren’t comfortable with. Locums tenens, as these doctors are known, cover around 15-20 days a month of on-call OB work at SageWest Lander, Whiteside said.

Until very recently, a group of providers — two obstetricians and two midwives — offered OB services through an independent clinic, and delivered babies at the hospital. A convergence of factors, from medical emergencies to burnout, reduced that number to zero.

That leaves Dr. Thomas Dunaway, who helms a private practice, as the only obstetrician for Fremont County’s general, non-tribal population. He employs a nurse midwife who also delivers.

The OB model of providers operating independently but delivering babies in the hospital is traditional in Fremont County, Whiteside said, and beyond his control. However, in light of the shortage, the hospital stepped in to recruit. It’s proven a challenging task.

In 2021 the hospital brought in Dr. Ken Holt, an obstetrician. Holt moved away less than two years later.

Holt jumped at the opportunity to practice in Wyoming, he said. He’d long dreamed of living in Wyoming, and when he and his wife moved to Lander in April 2021, they did so thinking they’d be here for the long haul. He started taking patients as a provider in Dunaway’s practice, then after a few months he and his wife opened their own practice.

Holt soon discovered major obstacles to running a successful practice in Lander. Namely, he said, the hospital itself. “For a physician who a significant amount of their practice involves utilizing the hospital, and you’re in a community that doesn’t wish to go to that hospital … to say that it’s challenging would be, you know, an understatement,” Holt said.

Patients would establish care with Holt, visit for prenatal reasons and then transfer care to another hospital, he said. That hurt his bottom line.

Unable to make it work, he closed the practice and moved away. Holt now works as an obstetrician in Arkansas. But the Wyoming experience was devastating, he said, particularly given Fremont County’s needs.

The hospital has recruited another obstetrician. The new doctor, hired directly as a hospital employee, will start seeing patients in 2024, Whiteside said. The hospital has also signed a family practitioner who can deliver babies, and is recruiting one more OB and another family practitioner. The goal is to have three providers for patients to select from.

Until then, however, Whiteside expects the hospital will continue to wrestle with the shortage’s negative side effects. “The bad outcome is what we see every day: Somebody showing up nine months pregnant with zero prenatal care,” he said.

Hurdles, hearts and minds

“Recruitment is tough here,” Whiteside said. It’s difficult to find a doctor with a spouse who both enjoy rural life. OB has more on-call pressure than other specialties — babies have notoriously unforgiving timing and doctors often deliver their patients even when they aren’t on call. That can equate to a heftier workload and lead to burnout.

“And that’s what’s happened to some of our doctors,” Whiteside said. Nursing recruitment is also a struggle, he said.

Dr. Travis Bomengen, a Thermopolis family practitioner who provides OB care at Hot Springs Health — where births have been on the rise — has been closely involved in the strategic growth of the Thermopolis hospital and its affiliated offices.

When they recruit, he said, they do so in a deliberate fashion with the goal of “retaining someone, not filling a position.” They’ve also started a residency program for early-career doctors as a way to attract physicians to stick around. It seems to work well, he said.

Among the challenges rural hospitals face is finding a balance between patient volume and the bottom line.

“Volume matters quite a lot,” said Josh Hannes, vice president of the Wyoming Hospital Association. “And in OB, you’re really staffing for capacity. So there’s a certain amount of cost whether you deliver one baby a month or 1,000 babies a month. You still bear that burden regardless, and it’s due to the overly complicated way health care is financed.”

In a vexing “Catch-22,” robust health care is a key ingredient needed to create the jobs and tax revenue that in turn drive patient volume and support the economics of rural facilities. “And so when you peel those pieces away from a hospital, you’re losing that downstream impact that supports your community,” Hannes said.

Wyoming Department of Health numbers indicate that 103 Fremont County babies — or nearly one in four — were born somewhere else in 2022.

SageWest Lander’s challenges will be difficult to overcome, said obstetrician Jan Siebersma, who stepped away from practicing OB at an independent clinic in 2022. Siebersma still provides gynecological care and works on-call delivery shifts at the hospital as a locums.

The Riverton OB closure and Lander’s sterilization flap upset some patients deeply, Siebersma said. “I think SageWest took a tremendous hit from all of that,” he said. “There are people in this community and certainly people in Riverton … that just flat out will not go to SageWest.”

Heidi Stearns, a retired homebirth midwife who delivered Fremont County babies until June, thinks part of the problem is the hospital has lagged behind progressive birthing techniques. Many modern birthing suites include laboring tubs, offer nitrous oxide for pain and allow vaginal births after c-sections, she said. SageWest Lander does not.

Like many Wyoming hospitals, SageWest’s bylaws stipulate that a nurse midwife must work under a licensed obstetrician, which means the midwife is covered under that OB’s liability insurance. It’s not a small ask. The OB must also be on call if the midwife is delivering, in case a c-section, which midwives don’t perform, is needed.

Tracy Rue, who is involved in economic development in Lander, sees SageWest’s profit model as problematic. “Unfortunately, at this hospital, their focus is money,” Rue told WyoFile.

Hospital leaders are trying to make inroads in the community, attending local meetings, addressing patient concerns, serving on boards and investing in the facility — including a new ultrasound machine for OB — Whiteside said. In 2022, SageWest added 22 affiliated providers and made more than $1.4 million in capital improvements, including new patient beds and monitoring systems, according to the hospital. But persuading the community may take time.

“It’s hard to undo a decade’s worth of negative reputation,” Whiteside said.

In the meantime, families continue to choose between risking travel to deliver elsewhere or the gamble of delivering with a doctor they don’t know. WyoFile will explore statewide solutions in the final part of the series next week.

DISCLOSURE: WyoFile Chief Executive and Editor Matthew Copeland is married to a former SageWest employee.

This story was made with the support of the Center for Rural Strategies and Grist, and is the third in a series examining the shortage of OB providers in rural Wyoming. Learn more about the Delivery Desert project and read the other parts here.

Do we expect profits from our police? Our fire crew? Our library? Our public schools? Our post office? Obviously, the answer is no. We expect access to safety, security, education and communication. And we pay taxes and help with fundraisers to make it happen. These services are so fundamental to the American experience that they are taken for granted.

And yet we haven’t adopted the same philosophy around health care. It’s a shame, and it’s a shortcoming of our society.

As it stands, a private equity firm based out of Kentucky owns Fremont County’s only labor and delivery unit. Not good. Furthermore, the government subsidizes critical access hospitals, so your tax dollars are helping prop up this profitable business model. Probably not good.

Childbirth happened 4 million times in 2021 in the USA per the CDC. Clearly, we need an effective safety net for pregnancy and care of the child. We need to do better.

Great article. For-profit hospital systems (and for-profit healthcare in general) literally causes suffering and death so that administrators and shareholders can make record profits. It’s such a shame to see a vibrant community full of young people who want to start families being held hostage by this situation. Women shouldn’t have to risk their lives with substandard prenatal care and childbirth experiences, or risk their lives by traveling long distances to have a baby, in order to live in Fremont County.

Dogged reporting, excellent writing. A terrific piece, Katie. Kudos.

Excellent story! Lander needs a community-owned hospital, hopefully Riverton is showing the way forward. Private equity vampires have no place in our (or any) community’s health. I wonder if there is a similar effort in Lander to take back our health care?

Katie,

Thanks again for an informative read. If the situation with obstetrics is that bad in these rural hospitals the other areas of care can’t be much better. I don’t envy these physicians having to deal with overbearing healthcare administrators who feel a duty to inject themselves into medical affairs.

Again, fabulous piece!

First, health care should NEVER be for profit!!! Second, the way he dismissess the cost to “commercial patients” because “insurance will cover it”. Hello…who does he think pays for insurance??? The patient who’s premiums & deductibles keep going up and benefits keep going down because of companies like his!!! When they charge insurance 8 x what they charge Medicaid, that means those patients pay 8 x more in “co-insurrance”, pay more towards deductible…that statement shows they don’t care about costs.

We have a for-profit hospital in Evanston and even if it had great care (most staff is great, but Dr care can be questionable), people avoid it because of the cost! We can travel within 45-60 min and get world class care at non-profit hospitals at a fraction of the price. Good on Riverton for taking matters in their own hands!

For-profit healthcare is destroying our healthcare systems.

Absolutely! Sir, you just hit the nail on the head.

I am a patient at Sage West Lander right now. I cannot comment on its obstetric services, but I have found all staff to be amazingly friendly and concerned with ow I am doing. There are what I’ll call structural weaknesses. For example, my blood culture taken two days ago had to be sent somewhere remote for analysis. My IV -delivered antibiotics can be fine tuned based on the results, but my doctor will not have those results today; maybe not even tomorrow.

Oh well, at least staff here genuinely care.

Just spoke to my doc. Results may not be available from Denver lab for another three days. This not only extends my stay, it prolongs the time I have broad-based antibiotics coursing through my system rather than more specific antibiotics. Ugh! Lab work like this used to be done here in Lander.

Great article! Sage West has crushed health care in Fremont county and it will never gain the respect or confidence of the people. It’s far more than just the OBGyn issue it is across the entire health care system. Lander was once had a thriving medical community that included even open heart surgeries. Now it is a shell of a hospital. The only way this changes is for Sage West to move out and get someone new. The new hospital in Riverton will probably make this happen. It’s sad that Lander once the medical center for Fremont county will lose this and now Riverton will have this too.

Katie, thank you for a very thoughtful, well-researched article. Never mind for high-lighting Wyoming’s need for quality healthcare services in our rural areas.

Private equity. All that needs be said.